FAQs

Unfortunately, a handful of exporters benefit from distracting you from the truth.

The Facts

At Stop Live Exports, we believe the public deserves the full picture. Below, we’ve answered some of the most common questions about live animal exports — from economic impact to animal welfare, legislation, and what’s next after the live sheep export ban.

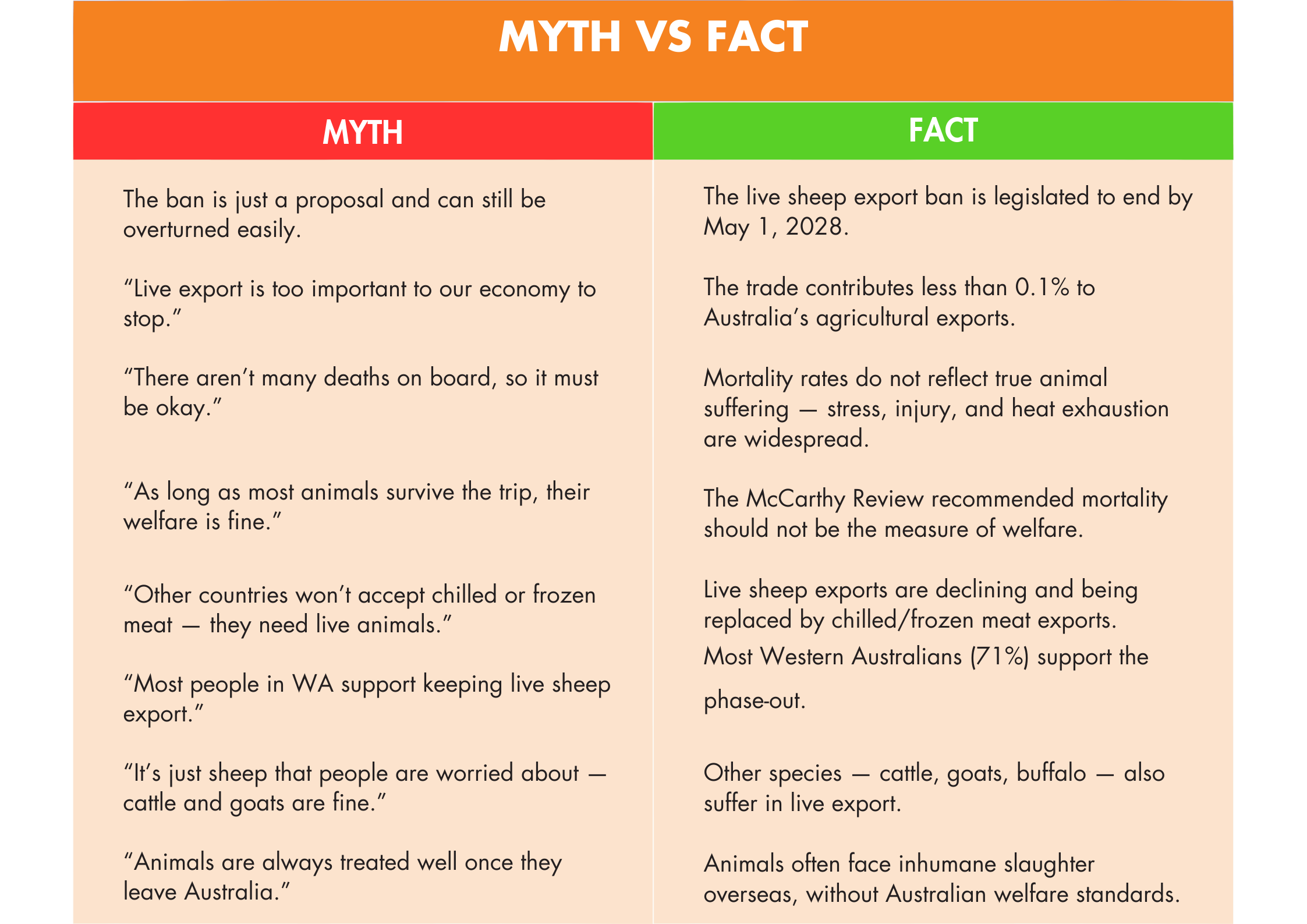

To begin, here are some of the most persistent myths we hear — and the facts that set the record straight.

What is the current status of live sheep exports in Australia?

What is the position of the Coalition on the live sheep export ban?

How does this ban affect Western Australia specifically?

The government has announced a transition package specifically to support WA sheep producers and associated businesses as they move away from live exports. This funding is intended to help the industry develop and expand more humane and sustainable practices, with a key focus on increasing onshore meat processing. This transition presents a significant opportunity for Western Australia to:

- Strengthen its domestic processing sector: Building more capacity for processing meat within WA means animals do not have to endure the cruelty of live export.

- Create secure local jobs: Onshore processing and related industries can provide stable employment opportunities within the state.

- Add value to agricultural products locally: Finishing and processing products in WA retains more of the economic benefits within the community.

While some industry figures have voiced concerns about the economic adjustments [Source: ABC News, Sheep Central, Agriculture and Food WA], the phase-out is a necessary step to end animal cruelty. The transition package is designed to assist the WA sheep industry in navigating these changes and to foster a more resilient, ethical, and ultimately more sustainable agricultural future for the state, free from the animal welfare issues intrinsically linked to the live export trade. The focus is on a managed and supported shift towards better outcomes for animals and the WA economy.

Why is Stop Live Exports and the majority of Australians against live sheep exports?

What support is being offered to farmers and communities affected by the phase-out?

Are there viable alternatives to live sheep exports?

Do consumers in the Middle East prefer live sheep so they can be sure the meat is Halal?

No — Halal-certified meat processed in Australia is widely accepted and compliant with Islamic requirements.

Australia has around 70 government-accredited Halal-certified abattoirs, where slaughter is performed under the Australian Government Supervised Muslim Slaughter Program. This program ensures that trained Muslim slaughtermen, approved by importing countries, are present and that animals are slaughtered in full compliance with Islamic principles.

Importantly, many Islamic authorities globally now accept pre-slaughter stunning, including reversible electrical and mechanical stunning methods, which ensure the animal is alive at the time of slaughter — a key condition for Halal compliance.

The belief that only live animals can be Halal is increasingly outdated. In fact, multiple investigations in importing countries have shown that slaughter practices used on live-exported animals often violate core Halal principles, including:

-

Killing animals in front of others

-

Binding or mistreating animals before death

-

Using improper tools and methods

-

Failing to minimise suffering

Meat from animals slaughtered under regulated, certified Halal conditions in Australia is more reliably Halal than that from animals killed in unregulated or abusive settings overseas.

In summary: Halal meat doesn’t require live export — and many Middle Eastern markets already import Australian chilled and frozen Halal-certified meat with confidence.

If Australia stops live exports, won’t markets just turn to countries with lower animal welfare standards?

Not necessarily — and Australia should never justify cruelty by pointing to worse practices elsewhere.

While other countries do export live animals, none offer the same volume, consistency, or reputation for quality as Australia. That’s why many importing countries have already transitioned to purchasing Australian chilled and frozen meat, which is reliably Halal-certified and comes with higher welfare assurances.

Australia’s participation in the trade doesn’t prevent cruelty — it legitimises it. By continuing to export live animals, we send a message to the world that such suffering is acceptable.

In reality, animals exported from Australia face some of the worst documented welfare outcomes. Voyages are long, stressful, and dangerous. Many Australian sheep are not well-suited to handling and transport due to limited human contact — making their suffering even more acute during loading, shipment, and slaughter.

Despite decades of attempted reform, systemic issues persist. From the thousands of sheep who died from heat stress in 2017 and 2018, to ongoing reports of brutal treatment abroad, it’s clear that no amount of regulation can make live export humane.

Ending Australia’s involvement sends a strong global message: we will not participate in or endorse a system built on routine suffering.

Aren't we an important source of protein for the Middle East?

All of the Middle Eastern countries which import sheep from Australia are wealthy nations and every country we currently export live animals to, with the exception of Turkey and Israel, also imports chilled beef and/or sheep meat from Australia.

What are the recent trends in the live sheep export trade?

What can supporters do to help ensure the phase-out is successful and humane?

What types of animals does Australia export live?

Why is Stop Live Exports concerned about all live animal exports, not just sheep?

Are cattle exports really "better" or more humane than sheep exports?

What are the main welfare problems inherent in all live animal exports?

- Stress and suffering during transport: Long journeys by sea or air cause significant stress. Animals are often confined in crowded pens, unable to move freely or lie down comfortably. They can suffer from motion sickness, injuries from rough seas or transport, and exhaustion.

- Inadequate conditions on board: Despite regulations, conditions on live export vessels can be poor. Ventilation may be insufficient, leading to heat stress, and hygiene can be a major issue, increasing the risk of disease.

- Lack of control over slaughter: Once animals leave Australian shores, we lose control over their treatment. Many importing countries have no, or poorly enforced, animal welfare laws, meaning animals can be subjected to brutal slaughter methods that would be illegal in Australia.

- Disease risks: The transport of live animals over long distances can facilitate the spread of diseases, posing risks not only to the exported animals but also to animal populations in importing countries and potentially even human health.

The live export industry claims it's economically vital. Is this true?

How effective are current regulations in protecting exported animals?

- Enforcement challenges: Monitoring and enforcing welfare standards on vessels in international waters and in numerous importing countries is incredibly difficult.

- ESCAS limitations: While ESCAS aims to ensure welfare standards in importing countries, breaches are common, and the system has been criticized for lacking transparency and robust enforcement. Animals often “leak” from approved supply chains into local markets where they face brutal treatment.

Acceptable losses: The industry still operates on a model that accepts a certain level of animal deaths during voyages as a normal part of business, which is ethically unacceptable.

Doesn't having a vet on board make it safer for the animals?

Sick or moribund animals are not routinely euthanised. Most animals who die on live export ships are found dead in their pens – they are not euthanised before they reach this point.

For the 2400 sheep who died during one voyage aboard the Awassi Express in 2017 or the 4179 sheep who died in a “heat event” aboard the Bader III in 2013, they suffered horrendously prolonged deaths – not many, if any, were euthanised. For each sheep who finally died from heat stress, there were likely another 10 or more who suffered.

The presence of a vet has no impact on rough seas, crowding, temperature extremes, high ammonia levels from the build-up of urine and faecal matter, 24/7 fluoro lighting and constant noise from both the ship’s engines and the ventilator/extraction systems — all exacerbate the risk of illness and injury. Causes of death at sea include heat stress, inanition (failure to eat – essentially, starvation), salmonellosis, respiratory disease and traumatic injuries requiring euthanasia.

Up to 1% of every consignment of sheep and 0.5% of cattle can die at sea before a government investigation is even triggered. On a shipment of 60,000 sheep or 8,000 cattle, that’s 600 sheep and 40 cattle respectively.

From Australia alone, we estimate that over 20 million animals have perished at sea over the past 30 years, and countless tens of millions more suffered.

What can I do to help end all live animal exports?

- Support organisations like Stop Live Exports and others campaigning against the trade.

- Contact your elected representatives (local, state, and federal) to voice your opposition to all live animal exports and demand stronger action.

- Educate others about the cruelty involved in the live export trade for all species.

- Make conscious consumer choices that support humane and local industries.

- Participate in peaceful protests and campaigns.

Popular Resources

Live sheep exports account for 0.1%

Source: Independent Panel Report, 2023

More than 7 in 10 Australians

Source: RSPCA Australia, 2024